FCA and PRA licenses (authorisations) and ongoing compliance support, training, recruitment. Contact us 7 days a week, 8am-11pm. Free consultations. Phone / Whatsapp: +4478 3368 4449 Email: hirett.co.uk@gmail.com

FCA and PRA licenses (authorisations) and ongoing compliance support, training, recruitment. Contact us 7 days a week, 8am-11pm. Free consultations. Phone / Whatsapp: +4478 3368 4449 Email: hirett.co.uk@gmail.com

1 CUSTOMER DUE DILIGENCE (CDD) – WHAT IS IT?

Definition

CDD comprises the gathering of all relevant information about a client’s affairs. This is the information that enables an organisation to assess the extent to which that client exposes it to a range of risks, including the risk of involvement in money laundering.

CDD is often referred to as Know Your Customer (KYC) information, although the terminology has developed, as KYC was often associated with the client identification process, commonly thought of as the ‘passport and two utility bills’ approach to CDD.

CDD is a far more holistic concept than basic client identification measures, and encompasses a wider range of information and processes, which need to be gathered, verified and assessed throughout a client relationship.

More particularly, CDD information generally comprises information on the following aspects of a client relationship.

- Who is the client?

- What is the geographical location of the client’s

- residence

- assets, and business interests?

- What is the nature of the client’s business interests/occupation?

- What is the commercial rationale for the relationship between the client and the organisation (what is the client seeking to achieve)?

- What is the client’s source of funds?

- What is the client’s source of wealth?

- What has been the historical pattern of the client’s relationship activity with the business, and has it been consistent with what was expected at the outset of the relationship?

- Is the current or proposed activity consistent with the client’s profile and commercial objectives?

2 THE VALUE OF CDD INFORMATION

There are two main benefits that result from obtaining CDD information. The first is to obtain it and use it to decide whether to acquire a prospective client; the second, which is what is usually referred to as CDD, is to use the information actively to facilitate the effective monitoring of client relationships for unusual and potentially suspicious activity.

The key to obtaining maximum value from CDD information is to use it. The mistake financial services businesses commonly make is to obtain and document CDD information, but then fail to refer to it before conducting transactions. Such mistakes can prove to be costly.

Consider the following example:

An offshore corporate service provider (CSP) manages and controls a client company that its files show was set up for investment-holding purposes. Three years after its incorporation, the company enters into an agency agreement for the procurement of contracts and receives large commission payments. No questions are raised by the CSP, which fails to take account of the CDD information on its own files that indicates that the company was not set up to trade.

It later transpires that the agency activity was illegal, and that the commissions received were the proceeds of crime. The directors of the CSP are asked to explain why they did not regard it as unusual for an investment-holding company that they were managing and controlling to begin trading.

They are unable to provide an acceptable explanation.

3 WHO IS THE CUSTOMER?

The application of CDD is required when an institution that is covered by the regulations ‘enters into a business relationship’ with a customer or, at times, potential customer. This will include occasional ‘one off’ transactions even though this may not constitute an actual business relationship as it is defined.

A customer is defined as a party or parties with whom a business relationship is established or for whom a ‘one off’ transaction is carried out. A business relationship is a professional, commercial relationship where there is an expectation by the firm that it will have an element of duration.

The important issues to focus on are that:

- even where there is no ‘business relationship’ but only a ‘one off’ transaction, CDD will still be required (there are exemptions for ‘one-off’ transactions below euro 15,000); and

- CDD will also be required where a business relationship is established yet there are no transactions (such as advisory services).

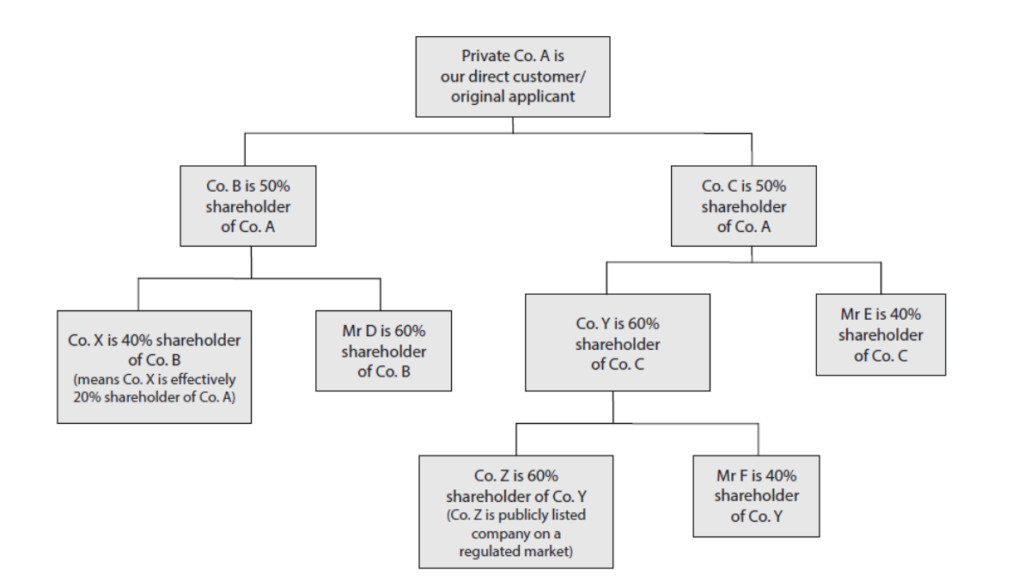

4 BENEFICIAL OWNERS

The principle behind this requirement is that criminals will attempt to disguise and/or hide the actual ownership of assets through the use of complex structures with numerous entities and/or beneficial owners.

The requirement is for firms to identify who the actual beneficial owners are and, on a ‘risk-sensitive basis’, verify the identity of such beneficial owners.

5 FOCUS ON TRANSPARENCY

The FATF’s February 2012 updated Recommendations gave considerable attention to the question of how to improve the transparency of legal persons and legal arrangements (and in particular trust arrangements) primarily in relation to assisting the investigation of money laundering and terrorist financing, but also with respect to what additional information might be made available to the private sector through various registries.

The updated FATF recommendations (numbers 24 and 25) call on jurisdictions to have reliable, accurate and timely information on legal persons and legal arrangements. In particular, the recommendations focus on the need to maintain additional information relating to beneficial ownership where financial institutions are used as a substitute for the underlying beneficial owner. In addition there are new recommendations requiring nominee directors and shareholders to disclose their status on the company registry, or be licensed, the aim being to reduce the risk of hiding the identity of the ultimate beneficial owner.

In the consultation leading up to the revised FATF recommendations concerns were expressed over the use of trust registries and the rationale for requiring the same level of transparency for a trust as for a legal person. FATF’s original proposal was to consider ‘protectors, enforcers and the like’ in the same way as beneficial owners.

The revised recommendations do allow jurisdictions to determine if a trust registry should be required. The focus now of the new recommendations is the obligation on a trustee to obtain and maintain adequate, accurate and up-to-date beneficial ownership information, including the identity of the settlor and the protector (if any) and they must disclose their status as trustees when entering into a relationship with a financial institution or DNFBP.

6 WORLD BANK RECOMMENDATIONS ON BENEFICIAL OWNERSHIP

The World Bank published a report in October 2011, The Puppet Masters 119 This report is a ‘must read’ for anybody involved with CDD policies and procedures at all levels. This report states that:

A formal definition of beneficial ownership is one that strictly delineates a set of sufficient conditions that qualify certain owners, controllers, and beneficiaries unequivocally as the beneficial owners of an entity or organisation.

This definition is formed on the basis of the assumption that, in the vast majority of situations, to be able to exercise ultimate effective control over a corporate vehicle or entity, an individual will require a measure of legally acknowledgeable authority.

This report goes on to examines how bribes, embezzled state assets and other criminal proceeds are being hidden via legal structures – shell companies, foundations, trusts and others. It also provides policymakers with practical recommendations on how to intensify current international efforts to uncover flows of criminal funds and prevent criminals from misusing shell companies and other legal entities.

The main recommendations made are that:

- governments should adopt a strategy to combat the misuse of companies and foundations to conceal ill-gotten funds;

- all providers of financial and corporate services to companies should collect beneficial ownership information about the company and continue to monitor whether this information is accurate;

- all corporate registries should provide a certain minimum standard of information on registered entities and allow for easy (online) searches of this information

- institutions should improve their investigative skills and capacity.

World Bank, The Puppet Masters: How the Corrupt Use Legal Structures to Hide Stolen Assets and What to Do About It [October 2011] http://issuu.com/world.bank.publications/docs/9780821388945?mode=window&printButtonEnabled=false&backgroundColor=%23222222

The recently updated FATF Recommendation number 10 requires financial institution to take steps to:

Identify the beneficial owner, and taking reasonable measures to verify the identity of the beneficial owner such that the financial institution is satisfied that it knows who the beneficial owner is.

For legal persons and arrangements this should include financial institutions taking reasonable measures to understand the ownership and control structure of the customer.

The clear requirement from FATF is that firms must get behind who actually ‘manages’ an entity.

In meeting this requirement, firms need to be aware of the risk to them behind such complex structures and probe sufficiently well to satisfy themselves that those claiming to be beneficial owners are, in fact actual beneficial owners and not acting on someone else’s behalf.

Some practical challenges to understanding who the customer is for CDD are:

- there are circumstances where a number of parties may be involved in a business relationship or transaction (for example with a syndicated loan) where for each individual firm they may not all be ‘customers’

- the actual CDD requirements to be applied in the numerous ‘customer’ type situations will vary, and

- working out exactly who are the beneficial owners within more complex organisation and entity structures may be difficult.

Practical approaches to all types of CDD and examples of more complex CDD situations, including beneficial ownership, are considered later in this module and potential solutions to these challenges are suggested.

7 ONGOING MONITORING AND CDD

While ‘on going’ monitoring of a business relationship is a general regulatory requirement applicable to transactions, it is also related to keeping the CDD information relevant and up to date. Again this is accepted to be on a risk-sensitive basis.

Ensuring that customer information is relevant and up to date is also a requirement contained within most jurisdictions’ data protection legislation and regulation.

There is no expectation for firms to re-verify the identity of a customer (unless there are doubts or new information – such as the previous identity document used is missing or no record of it has been retained or there is a new executive director or partner).

The idea of ‘on-going’ monitoring has resulted in the emergence in many firms of periodic customer reviews which, in a risk-sensitive environment, create their own challenges.

- What should such a review consist of?

- When should it occur?

- Should it apply to all customers?

It is clearly common sense to be able to identify when a customer’s behaviour would make a firm reconsider the money laundering risk associated with that customer (for example if they become a PEP, or there is adverse media information or they become the subject of a criminal investigation for financial crime). The challenge is how, in a risk-sensitive way, monitoring of customer behaviour as well as keeping customer data and information up to date can be made operationally effective yet efficient. We will consider this further throughout this module.

8 CLASSIFYING A CLIENT, CDD AND THE RISK-BASED APPROACH

Like all areas of firms’ AML regimes, regulation allows and expects a risk-based approach to be applied to CDD. In implementing a risk-based approach clients are typically categorised as lower, standard or higher risk.

This assessment results from:

- the collection of CDD information comprising both identification information and relationship information

- the preparation of a customer profile

- carrying out certain measures in relation to source of funds and source of wealth, and

- evaluation of the CDD information.

The FCA and many other regulators, as well as industry guidance, provide direction in this area by:

- mandating certain circumstances as ‘higher risk‘ requiring ‘enhanced due diligence‘

- setting out scenarios that could warrant an ‘automatic low risk’ categorisation, allowing for ‘simplified due diligence’

- providing guidance on the ‘ingredients’ firms should take into account when assessing the money laundering risk in other circumstances, and

- providing some assistance on the actual requirements for CDD in the various risk categories.

9 MANDATORY HIGH-RISK SITUATIONS – POLITICALLY EXPOSED PERONS (PEPs)

One of the most prominent risks to the financial services sector is the risk posed by public officials, their associates and family members. There have been a number of damaging high-profile money laundering scandals within the private banking sector that have involved PEPs, the most notorious in the UK being General Abacha of Nigeria.

The danger posed by PEPs is that a financial institution may be exposed to property that has been generated by corrupt practices. Regardless of any criminal or civil liability, which will undoubtedly arise, the high profile of such cases can expose any professional business or financial institution that becomes involved to an enormous reputational and regulatory risk.

PEPs have been defined by the Basel Committee CDD paper as:

individuals who are or have been entrusted with prominent public functions, including heads of state or of government, senior politicians, senior government, judicial or military officials, and senior executives of publicly owned corporations and important political party officials

The Basel CDD definition of a PEP extends to members of an official’s family, close associates and to any business (incorporated or unincorporated) with which the official has a relationship.

The European Fourth and latest, Directive, assists further by further defining PEPs (including domestic) as:

- heads of state, heads of government, ministers and deputy or assistant ministers

- Members of Parliament

- members of supreme courts, of constitutional courts and of other high-level

- judicial bodies whose decisions are not generally subject to further appeal,

- except in exceptional circumstances

- members of courts of auditors and of the boards of central banks

- ambassadors, chargйs d’affaires and high-ranking officers in the armed forces

- members of the administrative, management or supervisory bodies of state-owned enterprises.

‘Immediate family members’ includes:

- the spouse

- any partner considered by national law as equivalent to the spouse

- the children and their spouses or partners

- the parents.

‘Close associates’ are likely to include:

- any natural person who is known to have joint beneficial ownership of legal entities and legal arrangements, or any other close business relationship with the PEP

- any legal entity or legal arrangement whose beneficial owner is the PEP alone and which is known to have been set up for the benefit of the PEP.

This issue of the inclusion of ‘immediate family’ in the definition of a PEP has been tested in a March 2012 judgement in the Court of Justice of the European Union with some interesting conclusions. The full report is in a press release No 24/12120.

The court annulled a European regulation freezing the funds of Mr Xian Pai. He was included on a list of persons who benefited from the government of Myanmar’s economic policies via his father, the managing director of Htoo Trading Co and Htoo Construction Company.

His appeal was successful as he demonstrated there was no concrete evidence that he had benefited from his father’s activities. The court stated that

restrictive measures imposed on a third country must be directed only – in so far as natural

persons are concerned – against the leaders of that country and the persons associated

with them

…the application of such measures to natural persons solely on the ground of a family connection

with such persons who are associated with the leaders of the third country concerned –

irrespective of the personal conduct of such natural persons – is contrary to EU law.

120. Court of Justice of the European Union, Press release No 24/12 ‘Sanctions adopted by the Council in relation to a third party cannot be applied to natural persons solely on the ground of their family connection with persons associated with the leaders of that country’ [13 March 2012] http://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2012-03/cp120024en.pdf

This case is still to be fully ratified in the European Parliament but it serves to highlight the need to have complete, detailed and verified identification of source of funds and source of wealth when it comes to persons associated with PEPs. The court clearly laid the importance of this requirement in the comment:

Consequently, a measure freezing the funds and economic resources of Mr Xian Pai could have been adopted only in reliance upon precise, concrete evidence which would have enabled it to be established that he benefited from the economic policies of the leaders of Myanmar.

One significant challenge is whether to include ‘domestic’ PEPs in this definition. While most regulators only refer to ‘foreign’ PEPs, many financial services groups, especially those that operate across borders, have set aside this exclusion.

Before the recent FATF recommendations update countries were ‘encouraged’ to include domestic PEPs in their definition. The new FATF Recommendation 12 now includes the statement that:

Financial institutions should be required to take reasonable measures to determine whether

a customer or beneficial owner is a domestic PEP or a person who is or has been entrusted

with a prominent function by an international organisation.

Despite some confusion over different definitions of what a PEP is, many financial institutions already go beyond their legal requirement and do perform EDD on domestic PEPs in order to effectively manage the legal and reputational risk posed by such clients. It is worth noting that the draft proposals in the Fourth EU Money Laundering Directive extend specific requirements for domestic PEPs.

10 PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED WITH PEPS

The danger posed by PEPs is that a financial institution may be exposed to property that has been generated by corrupt practices. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has this outlined in their Articles 15-22:121

UNODC “United Nations Convention Against Corruption” [2004] http://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNCAC/Publications/Convention/08-50026_E.pdf

active bribery of national public officials; passive bribery of national public officials; active bribery of foreign public officials and officials of public international organisations; passive bribery of foreign public officials and officials of public international organizations; embezzlement, misappropriation, or other diversion of a property by a public official; trading in influence; abuse of functions or position by a public official for unlawful gain; illicit enrichment by a public official; bribery in the private sector; and embezzlement of property in the private sector.

Whether handling property derived from corrupt practices at home or abroad constitutes an offence of money laundering within a particular jurisdiction depends upon the definition of criminal conduct within that jurisdiction’s primary AML legislation. As recently as 1999, the US was the only country that had criminalised the paying of bribes abroad. The regulatory landscape is changing: the UK assessed the Bribery Act with its extraterritorial reach in 2012 and Russia signed the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in May 2011. The G20 have also firmly placed corruption at the top of their agenda with an Anti-Corruption Action Plan adopted at the Seoul Summit in 2010.

Although the number of countries prohibiting corrupt conduct is growing, the reality is that, when jurisdictions apply a single criminality test to offences of money laundering, bribery of foreign officials may not be a domestic offence in the country where it occurs and is therefore unlikely to predicate an offence of money laundering. Care must be taken in these jurisdictions.

Despite the inability of bribery of foreign officials to be a predicate offence of money laundering in certain jurisdictions, relationships either with companies that pay bribes or PEPs that accept them pose significant risks to all businesses and should be avoided. The reputational and regulatory damage that can result from a relationship with a corrupt PEP far outweighs any possible benefit that can be derived from such a relationship, however valuable it may be perceived to be.

11 DEALING WITH PEP RELATIONSHIPS

Perhaps the most prominent example of a damaging relationship between a PEP and financial institutions was provided by the allegedly corrupt former President of Nigeria, General Abacha, who is said to have diverted billions of US dollars in international aid for his personal benefit. The acceptance and management of funds from his family and friends prompted a report dated 30 August 2000 by the Swiss Federal Banking Commission (SBFC).

The report represented the culmination of an investigation into 19 banks that had accepted funds from the family and friends of General Abacha. The total sum deposited with the banks was approximately US$660 million. The report divided the 19 banks into three categories:

- Banks with irreproachable behaviour

- Banks showing weak points, and

- Banks showing more serious failings.

The report provides an interesting insight into the reasons why certain of the Swiss banks were deemed to have serious failings (and were therefore vulnerable) and concludes by emphasising the importance of CDD.

Swiss banks were not the only culprits; 23 UK banks were also implicated and the FSA’s investigation concluded that, generally, significant AML control weaknesses had arisen. A majority did not know who the ultimate beneficial owner of the funds was, in other words they did not know the true identity of their client, and failed to conduct any checks on the source of funds or wealth that they were handling. Doubtless, if the banks concerned had undertaken thorough CDD checks, the business would not have been accepted or suspicion reports would have been filed at an early

stage in the relationship.

The Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative (StAR) PEP report122 from the World Bank/UNODC also recommends that:

At account opening and as needed thereafter, banks should require customers to complete a written declaration of the identity and details of natural person(s) who are the ultimate beneficial owner(s) of the business relationship or transaction as a first step in meeting their beneficial ownership customer due diligence requirements (Recommendation 2).

StAR goes onto suggest that this should be a legally enforceable document, which would help discourage intermediaries, family members and associates of PEPs from engaging in bribery and corruption.

World Bank ‘Stolen Asset Recovery – Politically Exposed People’ [2009] http://www.assetrecovery.org/kc/resources/org.apache.wicket.Application/repo?nid=20d726d4-d8d8-11de-aed1-efa12ab4a114

StAR’s third recommendation goes on to say that:

Public officials should be asked to provide a copy of any asset and income declaration form that they have filed with their authorities, as well as subsequent updates. If a customer refuses, the bank should assess the reasons and determine, using a risk-based approach, whether to proceed with the business relationship (Recommendation 3).

Nearly 109 countries hold income declaration information on politicians and they are a very useful source of information for an MLRO. Global Witness recently published a report entitled international Thief: How UK Banks are Complicit in Nigerian Corruption which also highlighted the importance of understanding local legislation. Nigeria doesn’t’ permit state governors to hold foreign bank accounts, but several UK banks had missed this red flag. There are good reasons why this rule may be flouted but it should be part of the EDD process. The Global Witness report also recommends that financial institutions use income declaration reports to help identify PEPs. StAR published a report on just this subject entitled Income and Asset Declarations: Tools and Trade-offs in 2009.

The UK JMLSG Guidance mentions income declaration forms:

Firms may wish to refer to information sources such as asset and income declarations, which some jurisdictions expect certain senior public officials to file and which often include information about an official’s source of wealth and current business interests. Firms should note that not all declarations are publicly available and that a PEP customer may have legitimate reasons for not providing a copy. Firms should also be aware that some jurisdictions impose restrictions on their PEPs’ ability to hold foreign bank accounts or to hold other office or paid employment. (5.5.28)

The Third EU Directive suggests that a PEP is no longer a PEP one year after leaving office. The StAR report firmly disagrees with this and the UK JMLSG Guidance offers some practical guidance:

Although under the definition of a PEP an individual ceases to be so regarded after he has

left office for one year, firms are encouraged to apply a risk-based approach in determining

whether they should cease carrying out appropriately enhanced monitoring of his

transactions or activity at the end of this period. In many cases, a longer period might be

appropriate, in order to ensure that the higher risks associated with the individual’s previous

position have adequately abated.

It is also pertinent to note that the PEP definition was created to assist financial institutions in identifying people who are more exposed to corruption owing to their line of work. Strictly applying one definition over another misses the point. It is heartening to see that the JMLSG Guidance acknowledges this in section 5.5.21, where it states:

Public functions exercised at levels lower than national should normally not be considered prominent. However, when their political exposure is comparable to that of similar positions at national level, for example, a senior official at state level in a federal system, firms should consider, on a risk-based approach, whether persons exercising those public functions should be considered as PEPs.

Under the risk-based approach financial institutions should be asking what level of risk their client may expose them to regardless of what label can be applied to that client.

Knowing whether or not a client is a PEP is an essential element of CDD for all relationships. Many firms now employ databases to assist in the identification of PEPS.

The FSA thematic review of ‘Banks’ Management of High Money Laundering Risk Situations‘ published in 2011, has commented that firms need to seriously consider whether the use of such databases should be their sole method of identifying PEPs and that they consider additional methods to assist in this process (this report is examined in depth in section 18.1 below).

FSA ’Banks’ management of high money-laundering risk situations’ [June 2011] http://www.fsa.gov.uk/pubs/other/aml_final_report.pdf

This could be a relationship manager’s personal knowledge of the customer, which could be viewed as a critical source of information. In addition, a PEP may be identified through methods including:

- checking the names against external databases

- internet searches (such as Google) and

- newspaper/media reports.

Note that databases are merely tools to assist in identifying potential PEPs and any ‘hits’ can only be used as a reference or guide for determining whether an individual is actually a PEP. In addition, the absence of a match from online research is not a reason to ignore a PEP. Given the potentially high money laundering risk posed by PEPs, there are EDD requirements that should include an understanding of, as well as information and corroboration of:

- source of wealth (the economic activities that have generated the client’s net worth)

- source of funds (the origin and means of transfer for monies that are accepted for the account), and

- the commercial rationale for the arrangement/relationship.

It will be necessary to conduct enhanced continuous monitoring of a business relationship.

Additionally, PEP relationships should have ‘senior management’ sign off or approval. While there is no regulatory requirement, firms should consider the involvement of money laundering practitioners (such as MLROs) as well as making senior management part of the on-boarding approval process and any subsequent review relating to PEPs.

12 MANDATORY HIGH RISK SITUATIONS – CORRESPONDENT BANKING

Regulations in most countries require additional due diligence measures in relation to correspondent banking relationships.

Correspondent banking can be defined as:

the provision of banking-related services by one bank (the Correspondent) to another bank (the Respondent) to enable the Respondent to provide its own customers with cross-border products and services that it cannot provide them with itself, typically due to lack of an international network. In other words, a Correspondent is effectively an intermediary for the Respondent and executes/processes/clears payments/transactions for customers of the Respondent.

Money laundering risks in correspondent banking relationships arise because:

- the correspondent has limited information about the entire transaction

- the correspondent is often dependent on the due diligence processes conducted by its correspondent bank. The correspondent does not have a direct relationship with the underlying clients for the transaction and cannot therefore assess if the underlying transaction is consistent with the business profile of the client.

In the vast majority of cases where there is a relationship with another bank it is appropriate to treat it as a correspondent banking relationship. It is extremely difficult to identify and continually monitor for changes to circumstances where there may not be an actual ‘correspondent’ relationship, merely a ‘principal to principal’ relationship (where, for example, transactions are conducted between the parties – even if they settle through SWIFT (i.e. keys have been xchanged) or capital markets, foreign exchange).

The level of EDD requirements to apply to correspondent banking relationships should include considerations of and, as applicable responses from the respondents on some or all of the following.

- The AML risks in the country of establishment and the country of operation of the customer (whichever is higher)

- The transactions that the customer will support for its customers

- Whether the correspondent is a downstream correspondent clearer (i.e. the respondent that receives correspondent banking services from the correspondent and itself provides correspondent banking services to other financial institutions in the same currency as the account it maintains with its correspondent)

- Whether it gives its clients access to the firms’ correspondent accounts

- The businesses undertaken by the respondent, such as:

- private banking as sole business

- private banking/HNW wealth management alongside other

- business lines

- Internet only

- current account and third-party payments/wires

- trade finance

- The respondent bank’s customer’s customer base:

- retail customers – domestic

- retail customers – international

- corporate customers – domestic

- corporate customers – international

- financial institutions – domestic

- financial institutions – international

- MSBs/money transmission services

- shell companies

- The respondent bank’s ownership:

- controlled by a PEP

- publicly quoted on a recognised market

- The AML regulation to which it is subject:

- operating with an offshore banking licence

- operating in an equivalent jurisdiction

- parent is regulated in an equivalent jurisdiction.

In order to obtain credible responses to questions on the above points, firms should seriously consider using an appropriate questionnaire (something based on the Wolfsberg Questionnaire for correspondent banking). Firms also need to ensure their processes do not encourage a mere ‘tick box’ approach, with common answers being applied to the questionnaires year after year.

Any correspondent banking relationship will entail a higher level of risk and enhanced due diligence, albeit that depending on the other risk factors (country, ownership) certain due diligence could be obtained from publicly available sources.

13 AUTOMATIC LOW-RISK SITUATION AND SIMPLIFIED DUE DILIGENCE (SDD)

Most regulators now allow for a form of SDD in the lowest-risk situations.

For example, the UK JMLSG Guidance provides the following explanation of SDD:

Simplified due diligence means not having to apply CDD measures. In practice, this means not having to identify the customer, or to verify the customer’s identity, or, where relevant, that of a beneficial owner, nor having to obtain information on the purpose or intended nature of the business relationship. It is, however, still necessary to conduct on-going monitoring of the business relationship. Firms must have reasonable grounds for believing that the customer, transaction or product relating to such transaction falls within one of the categories set out in the Regulations, and may have to demonstrate this to their supervisory authority. Clearly, for operating purposes, the firm will nevertheless need to maintain a base of information about the customer.

It is unlikely that this concession can be relied on widely in an offshore environment and typically relates to products such as pensions and life assurance.

Simplified due diligence may be applied to:

● certain other regulated firms in the financial sector in ‘equivalent jurisdictions’ (those jurisdictions providing a level of regulation equivalent to EU standards and relevant for inclusion as a mitigating factor)

● companies listed on a regulated or recognised market defined under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) – Committee of European Security Regulators

● beneficial owners of pooled accounts held by notaries or:

● independent legal professionals

● UK public authorities

● community institutions

● certain life assurance

● certain pension funds

● certain low risk products

● child trust funds.

What this means in practice is that if the nature of business being conducted fits within one of the above categories a firm may apply a ‘lighter touch’ in terms of the extent of CDD undertaken. It should be noted, however, that the forthcoming EU Fourth Money Laundering Directive links the risk-based approach to the application of CDD. Simplified CDD measures can be used where lower risk is identified. A non-exhaustive list of factors and types of potentially lower risk is set out in Annex II of the Directive.

This approach may provide opportunities to reduce costs and remove paperwork from account-opening processes. For example, in respect of a simple term-assurance life insurance policy, minimal documents and information may be collected at account opening, with greater checks in place at the claim pay-out stage.

Nonetheless, it is important to note that any such decision must be carefully documented and be justifiable in the eyes of the regulators. An example of this challenge concerns ‘financial institutions’ and the apparent contradiction related to correspondent banking (see section 7 above).

14 ENCHANCED DUE DILIGENCE (EDD)

If a customer is assessed as being high risk, the risk-based approach requires that financial institutions carry out EDD measures. It should be noted that in determining a risk assessment for a customer, the presence of one factor that might indicate higher risk does not automatically establish that a customer is higher risk. Equally, the presence of one lower-risk factor should not automatically lead to a determination that a customer is lower risk. Most jurisdictions require that all PEP relationships are automatically classified as high risk and that non face-to-face relationships also be subject to EDD measures. The process of determining an appropriate risk assessment

should take into account the absence or presence of relevant factors, whether any compensating factors apply, and the CDD information held about the relevant person.

The sophistication of the risk-assessment process may be determined according to factors established by its AML/CTF risk assessment.

In practical terms, EDD will involve:

● „. taking reasonable measures to establish a customer’s source of wealth – source of wealth is distinct from source of funds, and describes the activities that have generated the total net worth of a person, i.e. those activities that have generated a customer’s income and property

● considering whether it is appropriate to take measures to verify source of funds and wealth from either the customer or independent sources (such as the Internet, public or commercially available databases)

● obtaining further CDD information (identification information and relationship information)

● taking additional steps to verify the CDD information obtained

● commissioning due diligence reports from independent experts to confirm the veracity of CDD information held

● requiring higher levels of management approval for higher-risk new customers

● requiring more frequent reviews of business relationships

● requiring the review of business relationships to be undertaken by the compliance function or other employees not directly involved in managing the customer

● carrying out stricter monitoring of transactions and setting lower transaction thresholds for transactions connected with the business relationship, and

● setting alert thresholds for automated monitoring at a lower threshold for PEPs.

The EU’s Fourth Directive indicates that enhanced CDD measures are required in high-risk cases. A non-exhaustive list of factors and types of potentially high-risk relationships is set out in Annex III of the Directive.

15 ASSESSING MONEY LAUNDERING RISK IN ALL OTHER CIRCUMSTANCES

Most regulators require firms to assess their own money laundering risk in all other cases and apply a risk-based approach to the level of due diligence to be applied.

This has seen many manifestations over the years of money laundering regulation. Some firms apply High and Low risk ratings, while others apply High, Low and Medium and still others categorise even further to High High, High Medium, and so on.

There is no ‘right or wrong’ categorisation provided the approach is proportionate to the overall money laundering risks encountered by the firm, depending on the type of business it operates (e.g. insurance, money transfer, e-Money, credit institution) and the scale of the firm’s operation (domestic, international and so on).

Such considerations will determine the level of ‘sophistication’ required for risk assessment and whether to employ the assistance of an automated system in the process. When a firm applies its risk-based approach, however, there is a regulatory expectation that a number of factors will be considered when applying that approach to all other customers. We will now examine some of these considerations.

16 UNACCEPTABLE RELATIONSHIPS

A firm, in considering money laundering risks, regulations and guidance may decide that certain types of relationship are unacceptable. Such an example, referred to by FATF, would be shell banks. A shell bank is defined as a bank that:

● „. does not conduct business at a fixed address in a jurisdiction in which the shell bank is authorised to engage in banking activities

● does not employ one or more individuals on a full-time business at any fixed address

● does not maintain operating records at any address

● is not subject to inspection by the banking authority that licensed it to conduct banking activities, and

● is unaffiliated with a regulated financial group.

Quite clearly, another example would be individuals or entities that are on relevant sanctions lists issued by countries in compliance with UN resolutions or to which countries have applied sanctions unilaterally (UK, US and others).

To capture such individuals and entities many firms now use name-screening systems and processes. In many situations these systems will also capture other ‘adverse information’ from media reports about other clients as well as PEPs.

It is a matter for firms how they use such ‘intelligence’ in their risk-based approach to CDD but it should seriously be considered as an ingredient in any risk assessment.

17 RISK RATING RELATIONSHIPS

Having determined those situations that are unacceptable, along with those that will require mandatory EDD or allow for SDD (see section 8 above) the large population remaining needs to be risk-rated on the basis of a number of factors, which may include:

● the product offering of the firm and those products taken up by a customer

● geographic risk (for example the country concerned may be renowned for narcotics production and/or distribution)

● the customer type (salaried, sole proprietor, specific professions and so on)

● whether the customer is resident or non-resident

● any adverse information gleaned from name screening

● the delivery channels offered (for example, no face-to-face interaction)

● the various segments with which a customer may be aligned (such as large multinational corporates, small to medium enterprises (SMEs), private banking)

● the customer’s type of business (cash intensive for example), and

● the length of time the customer’s business has been in operation.

There are a number of external reference points to assist in the determination of risk in these areas.

For instance, some risks relate to geography or jurisdiction and these can be assessed by means of:

FATF Mutual Evaluation Reports, Transparency International Corruption Perception Index (CPI), CIA The World Factbook, International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR), High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA), High Intensity Financial Crime Areas (HIFCA), FINCEN Jurisdictions of Primary Money Laundering Concern, countries subject to OFAC Sanctions.

18 PRODUCT TYPES – FATF TYPOLOGIES

This matrix of risk ‘ingredients’ poses many challenges for firms in assessing the level of money laundering risk each customer may bring to the firm, not just at account opening but also for ‘on-going monitoring’ and the need to keep customer information up to date.

It is for firms to determine how simple or complex this risk assessment should be. Some firms have automated systems with scoring weighted to take advantage of the risk assessment. Others have a more ‘binary’ approach where, for example, a customer involved in a high-risk business will automatically be rated high risk and be subject to EDD.

As mentioned above, whatever approach is applied should be clear and proportionate to the overall money laundering risks. The result of the application of a risk methodology is a customer base that has been suitably risk rated into those customers that are higher risk and require enhanced levels of due diligence, those that can be allowed a simplified level of due diligence and,

the balance, those that would have a normal level of due diligence applied to them – referred to as ‘standard due diligence’ in the UK.

19 TYPES OF RISK

Example: Product risk – high or low risk?

Corporate Treasury Forex Service

This involves the conversion and transfer of currency deposits, both for trade/commercial purposes and as part of speculative/trading strategy. Often large sums involved.

Given that the above product does have third-party payments, allows additional payments, is international in nature and often involves complex parties to the product it should be considered high risk albeit that cash is rarely involved.

Example: Product risk – high or low risk?

Pure Term Life Insurance

Benefit is paid on the death of the policyholder.

Given there is no early surrender value, the payments are by regular premiums with no third-party payments allowed, with longer term periods and additional fraud controls this product would be seen as low risk.

Example: Customer risk – high or low risk?

Company A is a Hong Kong-registered building group doing business in Hong Kong and Indonesia. It was founded nine months ago by directors and shareholders Johnny Quan and Carol Chan.

The level of risk will be determined by factors such as:

● whether either of these individuals is a PEP

● the fact that it is a new company

● the countries in which it does business, and

● the type of business.

Even if there are no PEPs in this scenario it could still be deemed high risk owing to the jurisdictional risk (derived in part from Indonesia’s poor rating in the Corruption Perception Index of Transparency International) and the fact that the building sector has some reputation of corrupt practices.

20 THE PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF CDD – CDD IN PRACTICE

It is worth repeating the fundamental reasoning behind CDD. CDD is the foundation of a good AML regime that assists in the prevention and detection of criminal activity and those behind such activity. As such it is important that firms ensure that they:

● have identified the customer (including beneficial owners)

● have verified that identity, and

● have kept on file sufficient up-to-date information and data (at least the reason for the relationship) on their customers to assist in the detection of potentially suspicious activity.

It is also expected this will be carried out in a risk-based way in order that firms can apply resources to CDD appropriately. For example, the level of CDD and resources applied to a salaried individual working for a multinational company who wants a credit card should differ considerably from that for an SME based in a country with a reputation for high levels of corruption and poor regulation, who is seeking a series of products including trade finance and large term deposits.

In some firms this may be relatively straightforward, if the customer base is small, the product offering is limited and the customer’s geographic footprint is limited.

21 THE INTERPRETATION OF THE REGULATIONS

A key area of challenge to many firms is the interpretation of what regulations mean when they use phrases such as understanding the ‘nature of business’ or the ‘purpose and reason for opening the account’. The first table below looks at how firms may consider explaining to those of their staff responsible for CDD how these could be interpreted.

| Regulatory expectation | Practical application |

| Understand the nature and details of the usiness. | A demonstration that a firm clearly does understand the customer’s business activities.

Generic descriptions such as general merchandising, general imports and exports, real estate, etc. are not sufficient. There should be more description, as in the following examples.

|

| The purpose and reason for opening the account or establishing the relationship | Demonstrate understanding of the customer’s need for the services and/or products to be provided.

For example:

In these cases the products that the customers will use could be: Trade Finance – (LCs), Export documentary collection, etc., Financial Markets – FX, bonds, interest rate swaps, equity derivatives, etc., ash Management – current account with cheque books, overdraft, etc |

| An understanding of the anticipated volume of activity for the products used by the customer | Demonstrate understanding of the how the customer intends to use the products that will be provided.

Consider providing a range of monthly activity for each product indicated. For example, Export L/Cs HK$, USD/Yen FX US$, Outgoing payments euro, $, etc. This could be determined from available information (e.g. copies of recent financial statements). |

| The source of funds | Demonstrate understanding of the origin of funds to be used/ received throughout the relationship. In practice that means the activity from which the funds are ultimately derived; e.g. the customer’s business activities or sale of assets.

Description such as ‘Business proceeds’ would be fine if there is information available, for example, financial statements demonstrating a business that generates such proceeds. For other customers more description is required, for example, proceeds from media business that generates £x of annual sales and has a record operating income of £y in 2011′. |

Table 5.1 Interpretation of CDD regulations

The next set of tables and situations provide practical examples of CDD that may be applied in most situations (excepting those already given above). These are only a theoretical example of a risk-sensitive approach to CDD. Firms should develop and design an approach dependent on the actual money laundering risk derived by an ML risk assessment, any subsequent customer risk-rating methodology employed and extant regulations or internal requirements.

| Individuals | Practical application |

| a. Full name

b. Current residential address (Note: PO box not acceptable) c. Date of birth d. Nationality e. Identity document number f. Nature and details of occupation/ employment g. Anticipated level and number of transactions h. The purpose and reason for opening the account (if not implicit in the products taken) i. Source of funds j. Source of wealth |

To verify the identity of the individual documents that describe

the full name and either date of birth or residential address are the desired method. in certain cases, the individual required to be verified is ‘well-known’ (e.g. a well-known businessman often in the public domain) and sighting of any document as mentioned above may not be always be practical. Although all efforts should be taken to obtain such documents, where this is not practical, reliance may be made on any publicly available documents containing photographs of the individual. 1. Preferred document to verify identity: a government-issued document which contains the name, photograph and either the residential address or date of birth. For example:

2. Other methods:

incorporating full name; and supported by,

Examples of ‘second’ document:

3. A PO box is not generally acceptable as a residential address. In those countries where PO boxes are commonly used, such as the Middle East, the residential address must, at the very least, be a recorded description. PO boxes are acceptable as mailing addresses. |

Other less common situations for Individuals:

| Individuals | Practical application |

| Non face-to-face opening of account. (Where customer

is not met personally while opening account, e.g. request through mail, Internet.) |

While the documents obtained and seen may be similar to those required in normal ‘individual circumstances’ it is important to try and obtain some independent corroboration, which may include having them certified by other banks, lawyers, accountants, diplomatic missions, Commissioners of Oaths or Notary Public, or allowing uncertified documents provided the first payment to the account is carried out through an account in the customer’s name with a bank from an equivalent jurisdiction. |

| Customers who cannot provide

standard evidence (Such as customers: in low-income groups; with legal, mental or physical inability to manage their affair; people under care of others; dependent spouses or minors; students, refugees, migrant workers; and prisoners) |

There are good reasons why such customers are unable to provide the documentation for verification, but they too are entitled to financial services and should not be excluded. In these cases, examples of alternate methods of verification that may be used include;

1. letter from relevant authorities, in case of recipients of government benefits/financial support such as unemployment benefit/old-age pension 2. letter from care home manager or employer 3. letter from prison authorities or police 4. letter from educational institution 5. a letter or statement of reference from a person of good social standing such as a doctor, a teacher, a lawyer, an accountant, certifying his knowledge that the person is who he claims to be is the lowest level of verification that is acceptable. |

Table 5.2(b) Practical examples of CDD – Individuals, less common situations

| Non individuals – basic information requirements | Practical application |

| a. Full legal name of customer | Privately and government-owned entities (corporates, partnerships, trusts, NGOs etc.) would typically require one of:

As with Individuals the guiding principle is that the documents used have been issued by the government, government body or agency or accredited/regulated industry body. |

| b. Full registered address (i.e. incorporation, formation, or

registration) in country of establishment including country |

| Non individuals – basic information requirements | Practical application |

| c. Registered number or other unique identifying number

assigned by government to the entity (e.g. taxpayer identification number) |

Using a risk-based approach there could be circumstances

where the following could be used to satisfy CDD verification requirements:

|

| d. Full operating address

(if different to registered address) |

See above |

| e. Country of operation/

customer’s primary place of business |

Does this (e.g. armaments industry) require special risk considerations? |

Table 5.3 Practical examples of CDD – Non individuals

| Type of customer | Privately owned’

Applies to private companies, partnerships and unincorporated businesses (Not falling under any of the Special Categories given below) |

| Considered CDD

requirements |

Information and

verification

Verification

2. Authority of authorised signatory(s) to open and operate the account |

| Consider enhanced

CDD Requirements |

Consider further Identity of one or more controlling directors (e.g. managing director), partner or proprietor – typically the director with authority to operate the account. |

| Practical application

considerations and challenge areas |

Where the customer

is a majority-owned subsidiary (i.e. more than 50% ownership) of regulated financial institution (FI) or listed corporate (regulated market). A streamlined process could be acceptable:

|

| Type of customer | Privately owned significant and well established private entities SWEPEs. |

| Considered CDD

requirements |

Information and verification

Verification: 1. Identity of customer entity. 2. Authority of authorised signatory(s) to open and operate the account. |

| Consider enhanced

CDD Requirements |

|

| Practical application

considerations and challenge areas |

Definitions

1. SWEPEs may be limited companies, sole proprietorships or partnerships. A SWEPE should have: i. a long history in their industry ii. scale iii. substantial public information about them and their principals and controllers with information on beneficial ownership (at 25% level) information in the public domain |

| Type of customer | Trusts, foundations and similar entities |

| Considered CDD

requirements |

Information and verification

Verification

|

| Consider enhanced

CDD Requirements |

Additional verification considerations

|

| Practical application

considerations and challenge areas |

To verify the Trust

Certified copy of Trust Deed (or equivalent instrument that established the trust, foundation or similar entity), or relevant register search in the country of establishment. To verify the trustee (or equivalent director/ officer): the appropriate CDD standards as per the entity type should be applied (if not individuals). Trusts/foundations that are dedicated to charitable purposes: consider applying risk rating applicable to charities. For all other cases, apply this requirement irrespective of whether the trust is privately, publicly or government owned. Record whether the trust/foundation is discretionary, blind, testamentary, or bare. Describe the purpose of the trust/foundation: e.g. inheritance planning, provision for spouse and other family dependents, preservation of family wealth. Where the trust/ foundation is supporting significant activities, describe those activities in detail and the l ocations in which the trust/foundation is active. Principal beneficial owners of trust:

|

| Type of customer | Non-government organisations (NGOs)/ charities, including religious

bodies and places of worship |

| Considered CDD

requirements |

Information and verification

Verification

|

| Consider enhanced

CDD Requirements |

|

| Practical application

considerations and challenge areas |

Non-governmental Organisations (NGOs) and Charities are defined as private (i.e. not government) non-profit organisations that pursue activities ostensibly in the public interest.

Example of key characteristics are:

The definition also includes private foundations that typically have few (or single) sources of funding (e.g. Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation) and that mainly make grants to other charitable organisations and individuals. Practical Application of verification Verification of the body as per the legal entity/ customer type (e.g. private companies, trusts, clubs or societies) Where such bodies are required to be registered as charity, verification of their charitable status should be based on the official charity registration document, or check against the relevant government body’s official charity register. Due diligence practical ideas Detailed description of the activities of the NGO or charity.

Consider reference checks. Reference checks may be by reference to referees provided by the NGO/charity, checks with the relevant government charity commission/ registrar. |

| Type of customer | Clubs and Societies |

| Considered CDD

requirements |

Information and verification

Verification

|

| Consider enhanced

CDD Requirements |

|

| Practical application

considerations and challenge areas |

Table 5.4 Practical examples of CDD – Different types of customer

The above tables set out a significant proportion of the types of CDD situation likely to be encountered, whatever the type of regulated industry in which a firm operates. The CDD requirements relate to individuals or legal persons and provide practical suggestions on how to undertake CDD in a risk-based manner.

Nonetheless, there are other types of customer that could introduce specific risks. This may be because they are required by regulation to have EDD conducted or because it is not entirely clear exactly who the customer is for CDD purposes.

Nonetheless, there are other types of customer that could introduce specific risks. This may be because they are required by regulation to have EDD conducted or because it is not entirely clear exactly who the customer is for CDD purposes.

22 SPECIFIS RISK

The examples below set out such ‘uncommon’ scenarios or those that pose particular risk situations that may require a distinct approach to CDD, and the level of CDD to be applied.

Example

Mrs A wishes to open a joint current account with her husband. She works in a call centre and her husband is an employed plumber. They are resident in the country where they are opening the account and will be depositing an initial sum of US$2,500. They expect to deposit around US$1,000 monthly from salary payments.

The above is a good example where a standard set of due diligence procedures would apply.

Example

Mr B wants to open current and savings account with an initial deposit of β12,000. He is a Philippine national but resident in the UK where he is a senior diplomat. This may well be an EDD scenario.

Whether Mr B is a PEP would have to be determined and if so this would require EDD involving a more in-depth consideration as to Mr B’s actual source of wealth.

23 SECURITIES SERVICES

For Securities Services accounts/relationships, the customer for CDD purposes is the party who has signed the service contract/agreement. They may be corporate investors, fund management companies, international broker/investment houses, trust companies, global or local custodians.

24 TRADE FINANCE TRANSACTIONS

Letters of Credit (LC)

For Import and Standby LC If you are the issuing bank then the applicant of the LC is your customer.

For Export and Standby LC, if you are the advising bank, the issuing bank is your customer and the beneficiary of the LC is not your customer for CDD purposes. Where you are the second advising bank, however (i.e. you have received an LC from the first advising bank with instructions to advise the beneficiary), the first advising bank is your customer.

If you are the transferring bank, the issuing bank is the customer and the beneficiaries of the LC are not your customer for CDD purposes. This is because the issuing bank has nominated you as the transferring bank and has authorised you to effect transfers at the request of the first beneficiary. The source of funds in such cases originates from the applicant of the LC, on whom the issuing bank would have performed CDD. Therefore, by doing CDD on the issuing bank you should satisfy yourself of the anti-money laundering controls of the issuing bank. In circumstances where the first beneficiary of the transfer LC (i.e. the middle party) instructs you to issue a new LC after deduction of the first beneficiary’s fees/commission before transferring to the second beneficiary, CDD should be performed on the first beneficiary.

If you are the confirming bank, the issuing bank is your customer. The beneficiary of the LC is not your customer for CDD purposes. Nonetheless, if the LC does not call for or allow confirmation and you add a silent confirmation, then CDD should be performed on the beneficiary.

If you are the remitting bank that is sending export bills and documents under LC for collection and no financing is required, the issuing bank is your customer and the beneficiary of the LC is not your customer for CDD purposes.

If you are the negotiating/re-negotiating/paying/accepting bank, then the issuing bank is your customer. The exposure arising from the negotiation/re-negotiation/acceptance/ deferred payment is booked under the issuing bank. The beneficiary of the LC is not your customer for CDD purposes.

Even so, where there are discrepancies in the Export LC document and you negotiate the document, the beneficiary becomes the customer for CDD purposes.

For LC acquisition, where you acquire LCs from other institutions that are insured and where the beneficiaries are your customer with CDD already in place then CDD on the issuing bank is not required.

Documentary collections

For import documentary collection where you are the collecting bank, the remitting bank who has sent you the documents with instructions is the customer. In some circumstances it is not practical to perform CDD on the remitting bank; in such circumstances CDD can be performed on the importer if it is not already an existing customer.

For export documentary collection where you are the remitting bank, the exporter is the customer. If the exporter is not known to you, the exporter is directed to take the documents to the exporter’s bank. The exporter’s bank may route the documents through you, if that bank has a relationship with you. CDD will be required on the exporter’s bank.

Bank-to-bank reimbursement

For Export LC, where you have been nominated as the reimbursing bank to honour a claim from the claiming bank, the LC issuing bank is your customer. Refinancing For LC where pre-arrangement on financing has been made between you and the issuing bank, the issuing bank is your customer.

Risk participation for trade

For sell-down of confirmation risk of the issuing bank, where you are the confirming bank, to another risk participating bank, the issuing bank and risk participating bank are your customers.

For purchase of confirmation risk of the issuing bank, where you are the risk participating bank, the issuing bank is your customer.

Import factoring

The typical flows of import factoring are as follows:

- an exporter in one country (seller) sells goods to an importer in another country (buyer)

- the seller raises an invoice that the buyer must pay against

- the seller assigns the invoice to a financial institution in the seller’s country

- the financial institution assigns the invoice to you

- you present the invoice to the buyer and demand payment.

For the purposes of undertaking CDD, the financial institution that assigns the invoice to you is the customer. The presentation of a third party’s invoice to another party for payment does not constitute a business relationship and thus, CDD is not required on the buyer.

25 RECEIVING BANK TO AN IPO OR RIGHTS ISSUE

Where you act as a receiving bank to an IPO or rights issue, the following CDD standards

would generally apply as a minimum.

The applicant to an IPO or rights issue is treated as your customer. This is because you, as a receiving bank, are facilitating the applicant’s investment in securities and may, if the issue is oversubscribed, return all or part of the applicant’s funds by way of a cheque drawn upon yourself. Undertaking CDD on the applicant would therefore be required. Exceptions could apply in the following circumstances: „. the application is for less than US$15,000, or „. the applicant’s funds are received from an account in the applicant’s name with a bank (or its parent) in an equivalent jurisdiction.

Example:

Bank A is the receiving bank on a rights issue arranged by Bank B on behalf of company X. In the first hour applications are received from Y Ltd (US$500,000), Z Ltd (US$50,000) and Mr H (US$10,000) CDD would be required on Y Ltd and Z Ltd. It could be that CDD was not required

on Mr H.

26 TRANSFER AGENCY AND PAYING AGENCY

In both transfer agency and paying agency services, your customer is the investment manager or debt issuer. The investment manager (transfer agency) is responsible for undertaking CDD on the underlying investors.

26 SYNDICATED LENDING: PRIMARY MARKET FOR SYNDICATED LOANS

Where you are the lead manager of the syndication, CDD must be undertaken on the borrower. If requested, you can certify the degree of ID verification conducted to the other syndicate members. CDD is not required on the syndicate members on the basis that such members do not enter into a relationship with you. Where you are a syndicate member, CDD must be undertaken on the borrower.

Depending on where the lead manager (or its parent/head office) is regulated you could consider relying on their completion of the CDD on the borrower. This will depend on your firm’s risk-based approach to reliance on other firms.

Example:

Bank A is the lead manager in the syndication of a loan to company X. There are three other banks (C, D and E) in the syndicate. As the lead bank in the syndicate bank A is required to carry out CDD on company X. there is no need for CDD to be conducted on Banks C, D and E.

27 SYNDICATED LENDING: SECONDARY MARKET FOR SYNDICATED LOANS

Where you are selling a counterparty’s entire loan or a portion thereof in the secondary market, CDD must be undertaken on the counterparty, i.e. the entity to which the loan is sold, as a business relationship has been established. If you are buying a portion or entire loan, then CDD must be undertaken on the entity from which the loan is bought.

28 FINANCIAL MARKETS TRADING AND SALE: CENTRAL BOOKING

Some products offered and used by customers may be booked centrally or and/or regionally on centralised systems. For example, currency options and interest rate derivatives are often booked in regional booking centres. The booking of deals in centralised systems is usually undertaken in one of three ways:

- locally – the deal is booked in the name of a local branch or office

- back-to-back – the deal is booked in the name of the local branch or office and back-to-backed with the central/regional booking centre, or

- direct – the deal is booked directly in the name of the central/regional booking centre.

Where the booking centre is the counterparty to the transaction, as is the case with direct transactions, CDD records must be held by it in respect of the counterparty. The CDD data held by the booking centre must be compliant with the legal and regulatory requirements of the booking centre.

29 FINANCIAL MARKET BROKERS

There are two types of brokers with whom financial markets deal. For CDD purposes, they are to be treated in the following way.

Name-passing brokers take no part in the transaction or trade between you and the ‘introduced’ counterparty. CDD would not normally need to be performed on the name-passing broker. Counterparties introduced by name-passing brokers are your customers.

No-name give-up brokers. Rather than introducing the counterparties to one another,

no-name give-up brokers deal directly with both counterparties. Therefore, no-name give-up brokers are your customers. They are usually subject to licensing by a regulator and, therefore, you may be able to be treat them as financial institutions and, in certain circumstances allow SDD.

30 SECONDARY MARKET TRADING IN BONDS

CDD should be undertaken on the entity to/from whom the securities are sold/bought.

31 SPECIAL PURPOSE ENTITIES (SPEs)/Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs)

It is quite common in the business of Project and Export Finance, Structured Finance, Structured Trade Finance and Asset Backed Securitisation that finance will be provided to a specially created Special Purpose Entity. An SPE, which can also be known as a special purpose vehicle, is an entity that can be in the form of a company, partnership or trust and is created or used by large corporates for a specific or limited purpose. An SPE will usually not have any operating history at

the time of the initial financing.

The CDD requirements for SPEs are normally satisfied when the following conditions are met.

- The identity of the applicant for business has been verified. This will usually be the entity leading the transaction (usually the sponsoring entity or originator).

- Records have been obtained to verify the legal status of the SPE and those that are authorised to bind the SPE to the transaction:

- a copy of the SPE’s company, search, or certified copy of Certificate of Incorporation/Partnership Deed/Business Registration Certificate

- aboard resolution or mandate

- a list of current directors/partners/officers.

- The purpose and nature of the SPE and the transaction, its source of funds and payment flows are clearly understood.

CDD on the other participants is not required, on the basis that the participants do not enter into a contractual relationship with you, a similar arrangement as that applying to syndicated lending.

In some circumstances the SPE is only incorporated a few days before the transaction begins. In such cases it could be legitimate to accept an undertaking from a reputable law firm or another regulated financial institution engaged in the formation of the SPE to provide documentation after the relationship is established. Such a law firm or financial institution may also confirm information in the absence of a company search.

32 CORPORATE ADVISORY MANDATE

CDD is to be performed on the customer that has awarded you a corporate advisory mandate.

Private equity: Investors

Investors in private equity funds operated or controlled by you are customers for CDD purposes and CDD must be undertaken on the investors.

Private equity: Investees

Entities in which you may invest or counterparties of the purchase or sale of shares with you are not customers for CDD purposes. In practice, you will not wish to damage your reputation by becoming associated with undesirable/inappropriate investees and counterparties and as such, though they are not customers, you should consider appropriate mitigating controls for such risks.

Funds

A fund is a vehicle established to hold and manage investments and assets and it will normally be a separate legal entity, formed as limited company and limited partnership. Where the fund is your customer and an account is opened in the fund name directly, for CDD purposes, it is to be treated in the following way.

Regulated funds are subject to and supervised for compliance with AML requirements; your CDD requirements for regulated financial institutions should be applied.

Unregulated funds are not subject to regulatory oversight and thus pose a higher risk. As such you should consider undertaking CDD on the unregulated fund and also on the parties involved with the fund, namely: the investment manager, sub-manager/ investment adviser (if appointed and delegated the responsibilities of managing/ investing part of the fund and/or who has entered into transactions on behalf of the fund), and the fund’s ultimate controller (where it is not the investment manager but someone else who controls the fund/assets in the fund).

Unregulated funds can have complex structures and consequently may appear to lack transparency of ownership and control. If the fund has complex structures (with a number of layers of entities), the fund’s ownership/control structure and any interrelationships between the entities should be fully understood, unwrapped and documented.

Money Service Bureaus

MSBs are generally defined as entities that:

- exchange currency (bureaux de change)

- transmit/remit money (or any representations of monetary value) by any means, and

- cash cheques which are made payable to its customers.

This definition could well be expanded to include the upcoming areas of those that issue stored value cards/traveller’s cheques or money orders as well as those that sell or redeem such products.

MSBs, by their very nature, introduce correspondent banking-like risks. They may also be less well regulated, have less experience managing AML risks than banks, and have less close customer relationships. All of these factors add to the money laundering risks associated with these customers.

In considering these particular risks, firms should ensure that they have adequate procedures and processes to readily identify such customers. Given the close association to the risks posed by correspondent banking, serious consideration should be given to their management being under the same business line as that which caters for correspondent banking relationships.

The CDD applied to MSBs should also be closely aligned with that applied to correspondent banking, if not enhanced further. Additional steps may also be taken, such as the examples below.

1. Obtain evidence of registration with the relevant AML regulator.

2. Increase the level of management sign-off for MSBs.

3. Require the highest level of sign-offs for those with PEP ownership.

4. Introduce a bespoke questionnaire for MSBs to complete.

5. Obtain a copy of AML/CFT & CDD policy and procedures of the MSB.

6. Record the names of all directors and conduct names screening.

7. Record the names of all executive management and conduct names screening.

8. Record the names of all beneficial owners identified in the EDD process and conduct names screening.

9. Conduct additional media searches using Internet search engines and/or other available media sources. The purpose is to identify whether there is any adverse media/negative news.

10. A visit to the customer’s main office could be undertaken by a suitable person (possibly from the firm’s financial crime risk team) or his/her nominee, who must meet their equivalent in the MSB and discuss the MSB’s AML programme.

Bearer-share-issuing customers

Bearer shares are stock certificates that are issued by corporate entities, including private investment companies (PICs). A bearer share is owned by the holder (the ‘bearer’). Issuing entities do not maintain a register of ownership, thus making it difficult to track the beneficial owners of the company.

This lack of transparency can significantly increase money laundering risks and you should consider those risks and the circumstances in which you would, exceptionally, allow customers that issue bearer shares (for example in certain businesses, such as shipping, they are issued for historical reasons). Given this heightened risk, suggested approaches to CDD in these cases may include: